The

Ship Has Sunk and the Sharks are Hungry

by Terry Bohle Montague

All rights reserved.

(Portions of this article have been excerpted from Courage in a Season of War by Paul H. Kelly and Lin H. Johnson, due to be released this year.)

“At home or abroad, on the land or the sea, As thy days may demand, so thy succor shall be.” How Firm a Foundation Hymn #85

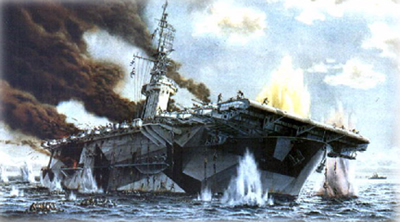

FREEDOM'S COST by R.C. Moore

(Used by permission of the USS Gambier Bay & VC-10 Assoc.

Inc. of Ohio)

On October 25, 1944, Earl Bagley was two weeks shy of his 34th birthday. He had a wife, Alice, three children, and a home in Idaho Falls, Idaho. But on that morning in October, Earl Bagley was aboard the USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73), in the Philippine channel, 90 miles north of Leyte and 60 miles east of the island of Samar, sailing on the deepest water in the world.

No one on the Gambier Bay knew, that October morning, the Center Force of the Japanese Imperial Navy was less than 25 miles away.

Three years earlier, Earl Bagley was worried about money. He had spent his youth helping support his widowed mother and brothers and sisters during the Depression. Then, as a young husband with small children, Earl worried whether he would be able to support them.

One night, just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Earl and Alice went to “the show” at a local movie theater. A short promotional film about the Navy was shown between features. It said the Navy was looking for men who had some background in math and electricity to train as technicians. Earl felt the same patriotic stirrings nearly everyone in the country felt at that time and considered one chapter on electricity in his high school physics text “a background in electricity”. Though Earl had not considered joining the military and did not expect to be drafted, the thought of training for a vocation worked its way into his thinking. It could be a better way to support his family while serving his country.

Earl dropped in at a U.S. Naval Recruiting Office and asked for more information. They told him he would have to take a battery of tests and, if he passed those and enlisted, he would be sent to Navy schools for nearly a year of training before going into any combat.

He decided to take the tests.

When the results came back, Earl was offered the rating of third class petty officer. With the Navy pay and its allotment for dependents, Earl would be making more than he ever had before.

Earl talked to Alice. It would be painful for Earl to be away from his family for that length of time and a challenge for Alice, but many families were doing it. Besides their feelings of patriotism, the incentive of training for a vocation, along with the Navy pay, made Earl and Alice think it might be worth the sacrifice. The pair considered it prayerfully. They went to their bishop for counsel and, after much discussion and prayer, decided Earl’s enlistment in the Navy was the right thing to do for their family.

Earl Bagley

To

Your Battle Stations

In November 1942, Earl

enlisted in the Navy for the duration of the war.

By December 1943, Earl had graduated from the Bliss Electrical School, the Radio Technician’s School, and reported for duty aboard the USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73), a newly constructed Carrier Vessel Escort.

In the fall of 1944, the Gambier Bay, as part of an eighteen-ship unit called Taffy 3, was afloat off the Philippine island of Samar. Taffy 3 was there to provide combat air and antisubmarine patrol for General Douglass MacArthur’s invasion on October 20th.

Five days after the beginning of the invasion, at 5 o’clock in the morning, the aircraft of the Gambier Bay had been routinely launched, and by six, many of the sailors were on their way to breakfast. The day had dawned stormy with poor visibility. Sometime between 6:30 and 6:45, the Taffy 3 Task Unit received a transmission from one of the pilots reporting unidentified ships south of their position.

The Task Unit Commander thought the pilot had seen part of Taffy 3's forces and ordered a dry run over the ships.

At a quarter to 7, the Task Unit received an “almost unintelligible and excited transmission.” The pilot flying the dry run had been fired upon. The Imperial Navy Center Force, believed to have been disabled and running from Admiral Halsey’s fast attack carriers, was 23 ½ miles from the Taffy 3 position and headed for them.

General Quarters sounded with a bell and the announcement that made everyone’s heart pound. “All men, man your battle stations!”

Pilots scrambled for their planes. Sailors leapt from their bunks, dressing as they ran for their stations. Others left their breakfasts uneaten in the mess hall. Many thought the emergency signaled an air attack but word came over the PA system they were about to be attacked by a surface fleet.

Earl wrote: “The enemy force had four large battleships, including the Yamato, the largest battleship ever built, capable of firing 18 inch projectiles. When the Japanese saw our little group of escort carriers they assumed we were the United States Third Fleet and reported us as large carriers and battleships. We were definitely outgunned.”

With the order to “Make maximum speed possible,” the ships of Taffy 3 began to run.

“Their cruisers and destroyers formed two columns and headed for us,” Earl wrote. “With their ships having a top speed of 30 knots and ours only 17 knots, we were at a distinct disadvantage. As the Japanese closed in on us, they began firing.”

Attacked

On the horizon, guns flashed

and large caliber salvos began falling around the Gambier

Bay. The men knew the gunfire came from three different

Japanese ships by the red, green, or white colors of the

geyser-like eruptions in the water.

“We began a zigzag course,” Earl wrote. “We had no place to go. Moving into Leyte Gulf would draw the Japanese warships there and trap General MacArthur. All we could do was stay out to sea. We launched as many airplanes as we could before turning to run. We were going with the wind and could neither launch nor recover aircraft.”

After the aircraft were up, the ships of Taffy 3 began laying down a heavy smoke screen to confuse the enemy. The Gambier Bay’s smoke screen used so much oil it interfered with the ship’s steam pressure and the ship began to lose speed. Then, the prevailing winds blew the smoke away from the ship, leaving it vulnerable to gunfire of the rapidly approaching Imperial ships. By that time, salvos fell on either side of the Gambier Bay. In the thinning morning mist, the men made out the distinctive match-stick shaped towers of the approaching ships, which, to every sailor’s dread, loomed larger and larger as they watched.

“With the Japanese on our heels, our ships turned to attack them. Though no match for the enemy, our destroyer escort made run after run and launched torpedoes, inflicting a great deal of damage on the enemy. Skillfully maneuvering the Gambier Bay, our captain dodged hits for over half an hour.”

At 8:10, the Gambier Bay suffered her first hit. It came down on the aft end, pierced the flight deck, and started a fire. Men scrambled for the fire hoses, but found, because of the failing steam pressure, they could get no water. The fire spread across the flight deck and onto the hangar deck, killing several men.

Three Imperial cruisers closed in on the port side, destroyers on starboard, and a battleship moved up from the rear. More salvos followed. The men heard the metallic click as the shells came over the water. At 8:20, a charge exploded below the water line at the forward engine room. The concussion knocked out the steering control and radar.

At 8:40, a shell pierced the skin of the ship. The engine room flooded and the crew was forced to abandoned it. The chaplain’s play-by-play over the PA system turned into a prayer. The thrumming of the ship’s huge engines ceased. The Gambier Bay lay dead in the water.

The Center Force, however, continued its attack. With each new hit, the ship shuddered so violently, men fell to the deck. Hot smoke, black and toxic, boiled around them while red- hot sparks, shrapnel, and flaming debris filled the air. A shell hit one of the planes that had not made it into the air. The plane’s torpedo exploded with a deafening roar. The ship’s deck boards shot through the air like spears.

Abandon

Ship

Many of the men did not hear the bell and order to abandon

ship, but with the ship listing 30 degrees to port, the

crew knew they had to get off the ship before it took them

all down.

When Earl realized they were going into the water, he hurried to his locker. There were things he would need; his white sailor’s hat as the equatorial sun shone with fierce heat and his shark knife and scabbard because there were man-eaters in the water.

Of that moment at his locker Earl wrote, “I had the most peaceful feeling come over me. Although I knew this was the end of the ship, I had no fear and knew that, whatever happened, I would be all right.”

In

the Water

Besides, he knew they would not be in the water long. The other

seventeen ships of Taffy 3 were in the vicinity and rescue

ships would be coming along soon.

The officers began dumping classified material overboard as the sailors abandoned ship. Ropes had been lowered and most men went down them hand-over-hand. Some slid down the ropes, suffering severe rope burns. Other sailors climbed down the cargo nets alongside the ship and then jumped into the water. Still others merely leapt overboard. Some came down on debris and other men already in the water. The able-bodied threw the injured overboard to make their way as best they could.

In the water, the men, single and in pairs, one helping another, swam with all their strength away from the dying ship. Most had swallowed oil and sea water and were vomiting. Many had burns over their hands, arms, and faces. From others with open wounds, their blood poured into the water.

Earl wrote, “From the catwalk, there was a rope extending from the bridge to within six or eight feet of the water. Grabbing it, down I went, hand over hand over hand, and immediately began to swim away from the sinking ship.

“After I had moved what I calculated to be one hundred yards from the ship, I stopped to look around. No one else was anywhere near. Attempting to inflate my life belt, I found there was a hole worn in it. There was nothing in sight to hold on to. As I rode up on a wave, I could see, about a quarter of a mile down tide, what looked like about a hundred men on rafts.

“I had to swim back around the ship to reach the other men.

“Nearing the ship, I noticed a raft hugging the hull about midships. A couple of men were trying to push it away. Swimming over to them, I found one of the men sitting on the side of the raft trying to push it away from the hull, the other was in the water pushing, but the tide was holding the raft tightly in place. I suggested we slide the raft along the hull and get clear of the fantail. In this manner, we were able to free the raft.

“I think we were only 150 feet from the ship when it rolled over on its side and sank. Ten or fifteen seconds later it suddenly shot up out of the water, stern first, to a height of about forty feet, where it seemed to stall as if deciding whether to go or stay, then disappeared into the sea.”

It was 9:11 a.m. The second commanding officer, Captain W.V.R. Vieweg, estimated the ship had been hit every other minute from 8:10 until she capsized to port and sank one hour and one minute later.

Earl Bagley was in the deepest water in the world with a hole in his life vest, but he knew he would be all right.

The life rafts, intended for 15 or 20, were far too few for the survivors in the water. Since the first concern was for the wounded, they were lifted into the rafts. The able-bodied survivors sat on the edges of the raft or hung along the sides.

The men assembled themselves into seven or eight groups of a hundred or more. They lashed their life rafts and floater nets together and collected flight deck planking and other floating debris to form makeshift rafts.

The raft Earl and his young shipmate had been pushing, was still distant from the others and Earl knew they had to join them as quickly as they could. When the boy, whose name was Barrett, got up on the raft, Earl noticed blood spurting from Barrett’s left leg, just above his knee. He had cut an artery in his leg without being aware of it. Working swiftly, Earl used Barrett’s belt for a tourniquet and emergency medical supplies on the raft to stop the bleeding. Then they headed for the nearest group of rafts.

“Each raft had a four foot aluminum oar in it,” Earl wrote. “By paddling and taking advantage of the tide, we caught up with the other rafts. The officers in charge were rearranging the men to keep their wounds out of the water as much as possible. There were about 140 of us. I was asked to leave the raft I was on and get on another. While swimming the fifty or sixty feet, I noticed we were surrounded by sharks.”

Imperial

Destroyer

Earl had safely gained the raft when a yell went up from one

of the men. An Imperial destroyer, steaming at full speed,

bore down on the flotilla. Everyone thought it had come

back to finish them off and they expected to be strafed

or have depth charges explode beneath them. The destroyer,

with its flag standing straight out from its mast, did not

slow as it approached the rafts. Instead, many of the destroyer’s

crew members saluted the men in the water and, to the surprise

of the Americans, several Japanese set up tripods and cameras

to snap photographs. The destroyer passed by the survivors

of the Gambier Bay, leaving them unharmed.

The last four verses of Section 89 in the Doctrine and Covenants sprang into Earl’s mind..

“And all saints who remember to keep and do these sayings, walking in obedience to the commandments, shall receive health in their navel and marrow to their bones;

“And shall find wisdom and great treasures of knowledge, even hidden treasures;

“And shall run and not be weary, and shall walk and not faint.

“And I, the Lord, give unto them a promise, that the destroying angel shall pass by them, as the children of Israel, and not slay them. Amen.”

Earl had kept the Word of Wisdom all his life and knew he had claim to that promise. He clung to it during the next several days. That, and the calm assurance he’d had as he stood before his locker. He knew he would be all right.

Urgent

Prayer

Earl’s thoughts turned to home, to Alice and their children.

He thought about how Alice might hear a brief announcement

over the radio about the sinking of the Gambier Bay

and he worried about how frightened she would be. Earl bowed

his head and sent up an urgent prayer that Alice would not

hear until he had a chance to tell her he was all right.

The crew discovered a serious problem with the emergency supplies stored on the life rafts. When the rafts dropped into the ocean, the water kegs popped their plugs and the kegs filled with sea water. The lack of fresh water became an increasingly desperate situation. Everyone was thirsty. The day was overcast with frequent rain squalls and the men tilted back their heads and caught the scant rain drops in their mouths. Earl also caught the rain in his cap to moisten the lips of the wounded.

He said, “Practicing the law of the fast throughout my life was important to me. I knew I could go without food and water for at least forty-eight hours and be okay. My experience with that practice gave me a confidence that most of my shipmates did not have.”

Sharks

The wounded began to die.

With so little room in the life rafts, there was nothing

to be done but remove the identification tags and bury the

dead in the sea.

The circling sharks were a constant menace and seeing their fins break the water terrified the crew members. They attempted to drive off the sharks by slapping the water.

Earl wrote, “At least two men were killed by sharks the first day. One of them was my friend, Lieutenant Buderus, the officer in charge of the Combat Information Center. His raft was so overloaded that some of the men were hanging around its outside. The Lieutenant thought he should take his turn. A shark bit him across the buttocks and down his legs. The men were able to get him onto the raft, but he died a short while later.”

The men knew other ships and aircraft from Taffy 3 were somewhere in the vicinity and, with a rescue party certainly launched, everyone expected a speedy rescue. They watched two of their own planes pass over, apparently without seeing them. A couple of hours later, two other aircraft flew over but missed seeing them again. Later, the men learned the rescue craft had the wrong coordinates.

And, adrift in the Pacific, the Gambier Bay crew did not know of the encounter taking place in Leyte Gulf between the biggest and the best of the Japanese Imperial Navy and Gambier Bay’s sister ships of Taffy 3.

The day faded into night, as the sailors waited and watched.

“Although the day had been warm, I shivered all night.

“During the night, my position on the raft was changed from the side to an end seat next to a corner. A large white box, presumably filled with medical supplies was lashed outside the raft near my left arm. About three feet behind my right side was a one-man rubber raft, in it was Barrett, the man with the injured leg who had been with me on the first raft. He was unconscious and I was to care for him should he need attention.

“The combined weight of the Red Cross box and some of us heavier men kept the raft on a downward slope to our end so I constantly bobbed in and out of the water. I had to hold on to the raft with one hand all the time to keep from sliding into the water.

“The leaky life belt I was wearing had filled with water. I was glad I had not taken it off. It was cumbersome to swim with, but I was grateful to have it, as I continually had two or three sharks poking their snouts into my back. Without the belt’s protection, one of them might have taken a bite of me.

“ The only way I could keep them away was to slap the water beside their heads. They did not like the concussion and would back away about a yard. As soon as I stopped slapping, they moved up close and began nudging me in the back again.”

The morning of the 26th, the Pacific Ocean stretched out from one horizon to another. The raft flotilla had drifted apart so groups lost sight of each other. Everyone watched the skies and the horizon for their rescuers. Everyone felt the effects of exhaustion, heat, hunger, and dehydration.

“Some of the men took sips of salt water which caused them to become delirious. Some of them thought they saw land and began swimming away. That was the last we saw of them. Many of the men had hallucinations and had to be given morphine to quiet them. Some died after drinking the sea water.”

How

Firm a Foundation

The sun shone hot and bright over the deep water of the Philippine

channel that day. A few men, exhausted from trying to stay

afloat, stripped down to their underwear and suffered serious

sun burns. Some tried to protect themselves from the sun

by cutting the legs from their dungarees. They cut eye holes

in the legs and pulled them over their heads. That worked

well enough until the salt-saturated fabric dried and became

painfully abrasive.

Everyone wondered what had become of the rescue teams. Earl watched the skies and the horizon and prayed that Alice would not hear an announcement about the ship.

“During the time we were in the water, and as time began to grow long, and there seemed to be doubts about our being found in time, my thoughts were of the gospel. The words of the hymn, How Firm a Foundation looped through my mind.

“In every condition, in sickness, in health,

In poverty’s vale or abounding in wealth,

At home or aboard, on the land or the sea,

As thy days may demand, so thy succor shall be.”

Earl took comfort in the message of the text. On this sea and during this demanding day, he clung to the promise that he would continue to be protected. He was adrift on the Pacific without food or water, surrounded by thousands of sharks, but he knew he would be all right. He prayed that Alice would be, too.

The inflatable life raft on which Barrett lay unconscious began to lose air and ,frequently, Earl unscrewed the valve core to blow it up again.

“Barrett was wearing white socks,” Earl wrote, “and his feet extended just a little over the end of the raft. His socks, though out of the water, attracted the sharks. Between the white socks and the white medical supply box, just a few feet apart, I think I had practically all the sharks in the area following on my corner.”

Someone opened a can of meat that had been in one of the survival canisters and each person got a small slice along with a dried biscuit.

“When I ate the salty meat, my throat constricted because I was so dehydrated and it took some minutes until I could breathe normally. That was all the food we had for two days.

“Someone threw the empty can into the water. The sharks grabbed it and began playing a game of tag. One big boy grabbed it, then spit it out; then another and another. As their jaws snapped shut on the can, the sound was vicious. Six or seven of the larger ones participated. This went on for about ten minutes. It gave me a little rest from slapping the water. Soon enough, however, I was back to the routine and preparing myself to go through another night.”

After two days and a night in the ocean with no shelter from the scorching sun, no food, water, or sleep, many men suffered from profound exhaustion. Some of those hanging on the outside of the rafts slipped into unconsciousness. To save their lives, other men held their shipmates’ faces above the water.

Again, the comforting text of the hymn formed in Earl’s mind.

“When through the deep waters I call thee to go,

The rivers of sorrow shall not thee o’erflow,

For I will be with thee, thy troubles to bless,

And sanctify to thee thy deepest distress.”

Rescued

During the second night,

sometime between 1 and 2 o’clock, the men in Earl’s

group spotted, in the distance, lights flashing coded messages.

“Our signalman could not stay alert long enough to send or receive a message. Our Executive Officer suggested to the Captain that we cut our raft loose and paddle toward one of the ships to find out if it was Japanese or American. About 0300, we paddled up to the ship.”

With great gratitude and relief, Earl saw that, “It was one of our landing ships.” He knew then, the fulfillment of the hymn’s last verse.

“The soul that on Jesus hath leaned for repose

I will not, I cannot, desert to his foes;

That soul, though all hell should endeavor to shake,

I’ll never, no never, no never forsake!”

“They immediately began to board us. Men crowded the ladder. One of them flung out his arm. It hit me across the chest and knocked me backwards into the drink. My first reflex was to look for sharks. But there were none.

“I was the next to the last man to board, just ahead of our Exec.”

Earl Bagley was all right.

Through that night and the following morning, the remaining survivors of the Gambier Bay were located and rescued through the efforts of three ships, the USS Samuel Roberts, USS Johnston, and USS Hoel. In the dark of night and in waters shielding enemy submarines, the three searched with their lights aglare and communications open. Their rescue efforts made them sitting ducks for the enemy.

Of the nearly thousand crew members of the USS Gambier Bay, almost eight-hundred men survived the sinking of their ship and two days and nights in the Pacific Ocean. Shipmate Barrett was not among them.

The aircraft launched from the USS Gambier Bay landed at Tacloban Island.

The other ships of Taffy 3, and aircraft from another unit, Taffy 2, attacked the Imperial Center Force and stopped it. Two Imperial cruisers, the Chikima and the Chikoi were sunk, many others damaged, and the rest of the fleet turned back by the determined men of the Taffy escort carriers, destroyers, and destroyer-escorts.

Alice

at Home

Back home in eastern Idaho, everyone gathered around their

radios everyday for the 5 o’clock news on KID. The

day the sinking of the Gambier Bay was announced,

Alice and her children had failed to turn on their set.

Earl’s cousin, Duane Higbey, did hear the news and went to the Bagley home. When he saw Alice and the children did not know about the Gambier Bay, he decided not to tell them. Neither did any member of the community mention it to Earl’s family. Alice only heard about it in a letter she received from Earl several weeks later.

Earl Bagley was reassigned to the USS Bedford Victory, an ammunition cargo ship. One year to the day of the sinking of the Gambier Bay, the Navy mustered out Earl and sent him home to his family in Idaho Falls where there were no sharks.

The Gambier Bay received four battle stars and shared in the Presidential Unit Citation to Taffy 3 for extraordinary heroism in the Battle of Leyte Gulf off Samar.

Earl and Alice became the parents of two more children. He worked in accounting and as an office manager until he retired at 70.

Brother Bagley served as Stake Missionary, Sunday School Superintendent, Stake Young Men’s President, Bishop, Branch President, High Councilor and Stake Patriarch.

He had been a leader in scouting from the time he was 17 and received the Silver Beaver Award.

Eventually, the Bagleys relocated to Salt Lake City, Utah. Earl enjoyed singing and playing the harmonica in a fiddler’s band in the Salt Lake Valley. He passed away on January 1st, 1984, at the age of 73.

Sources

Courage in a Season of

War, by Paul H. Kelly and Lin H. Johnson.

Bob Potochniak, Webmaster, and Tony Potochniak, a Gambier Bay survivor at seventeen years old, Historian.

Interview with Bonnie Bagley Anderson, June 2002.

Interview with Dean Bagley, June 2002.

How Firm a Foundation, text attributed to Robert Keen, ca.1787, music: Anon., ca.1889,

For more information about the USS Gambier Bay, or for information on how to purchase a print of “Freedom’s Cost” by R.C. Moore, go to http://www.ussgambierbay-vc10.com/

- Used with permission.

Terry

Bohle Montague is a graduate Brigham Young Universtiy and a freelance

writer, having written for newspaper, magazines, television and

radio. Currently, she is an editor at Meridian Magazine and writes

the Extraordinary Stories column.

Terry

Bohle Montague is a graduate Brigham Young Universtiy and a freelance

writer, having written for newspaper, magazines, television and

radio. Currently, she is an editor at Meridian Magazine and writes

the Extraordinary Stories column.